Scapegoat Wilderness

When any swath of land enters the National Wilderness Preservation system it is cause for celebration. On August 20, 1972, Congress passed Public Law 92-395 and Montana’s Scapegoat north of Lincoln gained this lofty designation. Now is a time to take a look back with great pride, for the Scapegoat is a special case. This is a citizen’s Wilderness, and it became reality in the face of stiff U.S. Forest Service opposition. The protection gained was the result of an immense amount of public outcry and involvement. Voices from both sides of the political aisle lined up to support it.

The struggle is a colorful and heart-warming story. If it hadn’t played out, the nation would have lost forever a cherished piece of her heritage.

When compared to other Montana wilderness topography, the Scapegoat doesn’t quite stack up as high on the majestic scenery scale, as it features only one geologic masterpiece. Simply put, it is a pleasing wilderness, providing easy access and a wonderful wild country experience. Well before it garnered national attention, generations of folks from Lincoln, Helena, Great Falls, Missoula and other nearby Montana communities found enjoyment and solitude in what was known to all as the Lincoln Backcountry. Its unroaded and untrammeled character added to the rugged individualism of those who chose Lincoln, an isolated place up until the late 1950s, as home.

The original Lincoln Backcountry was a 75,000-acre stretch of undeveloped Helena National Forest administered lands. The boundary reached south to within 12 miles of Lincoln and on the north touched the fabled Bob Marshall Wilderness. The 240,000-acre designated Wilderness of today sprawls over an area straddling the Continental Divide and reaching out to the inner segments of the southern Rocky Mountain Front. A landscape designated on its own as a wilderness, it is part of the greater Bob Marshall country consisting of the Scapegoat, Bob Marshall and Great Bear wilderness areas. This, the crown jewel of America’s wild assets, contains 1.5 million priceless acres of protected mountains, meadows and forests and almost one million acres of surrounding de facto wilderness.

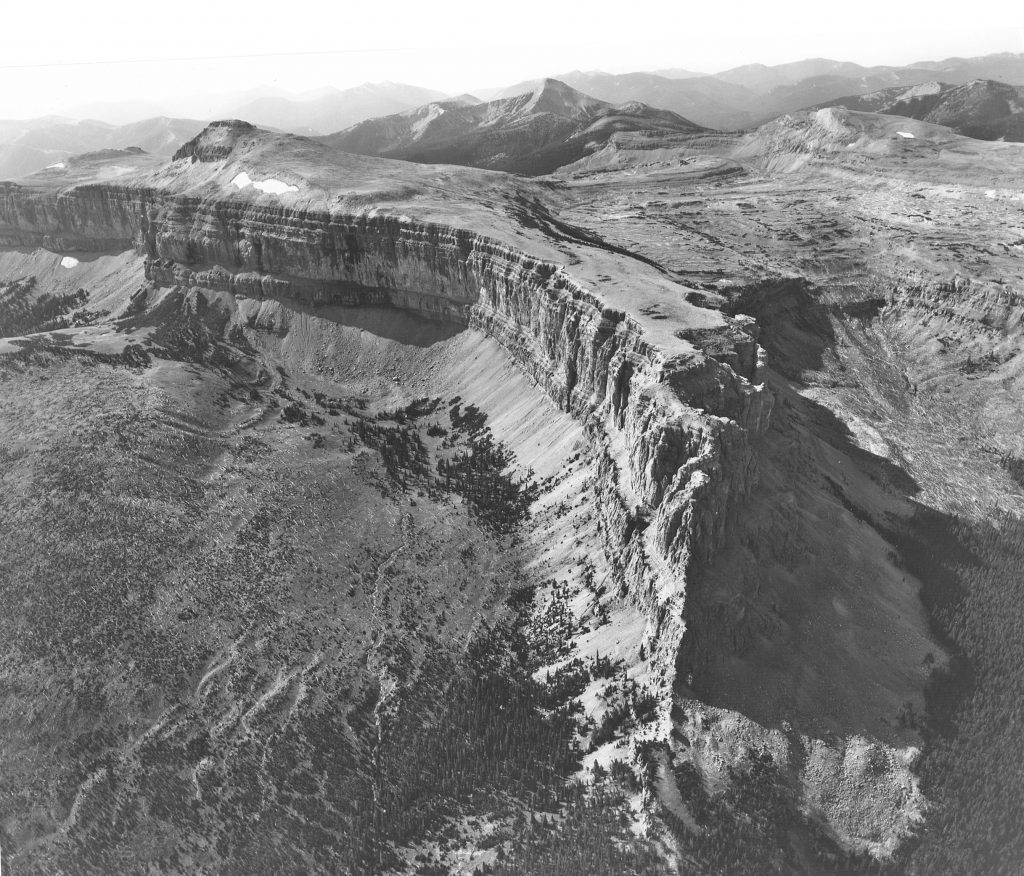

Scapegoat’s dominant feature and the destination of most foot and horse travelers is its namesake, Scapegoat Mountain, a 9,204-foot-talllimestone reef. The peak itself is merely a bump on the magnificent three-mile-long massif honeycombed with caves. The reef’s walls are sheer on almost all sides with access to the plateau restricted through the Green Fork drainage on the east and a few places on the west side. This somewhat level strip then rises on the north end to 9,079-foot Flint Mountain, the northern tip of the Scapegoat formation.

In the Green Fork, a stream pours out of the wall like a faucet. The cave behind it is reported to be about two miles long.

Half Moon Park, a beautiful place to camp, is immediately below the north and east side of Scapegoat Mountain. Here, an old burn has opened up views to the east. A great experience is to be snug in your tent when a summer storm is passing through. The thunder is amplified as it ricochets off the more than 1,000-foot-high walls of the amphitheater, creating a booming, percussion symphony.

Access to the Scapegoat is usually from the east by way of Elk Pass, the Dearborn River, Smith Creek or the Benchmark area. From the south and west side, approaches to the mountain and plateau are from the Danaher, the North Fork of the Blackfoot River and Lincoln. The Dobroda Creek headwater area, reached by trail from the North Fork of the Blackfoot Valley, offers one of the better ways to climb Scapegoat from the west. The same route also passes Tobacco Valley and McDonald Meadow, two scenic places south of the Southern end of Scapegoat Mountain. A 1988 forest fire opened up much of this country.

Day walkers, horseback riders and weekend backpackers favor 9,411’ Red Mountain, the highest summit in the Scapegoat and in the Bob Marshall country, and Heart Lake on its north side. The trailhead is reached by a road up Landers Fork, a tributary of the Blackfoot River east of Lincoln.

Caribou Peak and Big Horn Lake, on the Continental Divide, are two other prominent Scapegoat landmarks. Several trails approach the peak and lake. One up the West Fork of Falls Creek on the Rocky Mountain Front is the most commonly used path. A scramble up 8,401-foot Crown Mountain on the Rocky Mountain Front off of the Benchmark Road out of Augusta is rewarded by a great view of almost the entire bulk of Scapegoat Mountain and a good portion of the wilderness. Three important waterways are born in the Scapegoat. Just south of the “summit bump” of Scapegoat Mountain, a spring gurgles out of the plateau’s porous limestone and commences the Row of the Dearborn River. The Sun River gathers its initial waters from the northeast side of Flint Mountain. Below the southern perimeter of the Scapegoat wall, Dobroda and Cooney creeks join to send the North Fork of the Blackfoot on its way to connect with the main river in the Blackfoot Valley.

According to Cecil Garland, “patron saint” of the Scapegoat, the prairie and Rocky Mountain Front around Augusta were at one time almost overrun with sheep. The sheepherders who summered their herds in the mountains named almost everything in the area, including Scapegoat Mountain.

Over the years, the small town of Lincoln became known as a base of operations for commercial packers and guides and an entry into the Lincoln Backcountry and Bob Marshall Wilderness. By word and deed, the regional and national reputations of the outfitters grew, and so did that of the land they worked in.

As the Lincoln District Ranger and the Supervisor of the Helena National Forest, two enthusiastic users and stewards of the backcountry, who had both been on the job for nearly 20 years, prepared to retire in the late 1950s, new plans were being laid in the Forest Service Regional Office in Missoula to develop a system of roads that would open this special landscape to timber harvesting and campground construction. One could say the “custodial” era was ending and the “management” period was about to start.

In response to this threat, the Lincoln Backcountry Protection Association was formed to try to stop the development. Cecil Garland, who became the association’s president in 1962, operated a hardware and sporting goods store in Lincoln and had worked four summers as a campground foreman for the Forest Service, resigning when he realized he could not pursue his goals from within the agency. Cecil would be primarily responsible for the Scapegoat Wilderness Act of 1972.

Garland remembers his reaction to the possible implementation of the development plan. “A young Forest Service engineer came into our store in Lincoln and told me the USFS had abandoned a full survey of the road to the Lincoln Back Country and was now running only a flag line in their haste to build the road and quell the opposition. This young engineer in despair also told me that a bulldozer was sitting at the end of the road.

“I knew that time was short and called Congressman Jim Battin … I poured out my heart to him in a most pleading and earnest manner. He must have understood for he said he would help me … Battin then phoned Regional Forester Boyd Rasmussen and asked if he could have ten days to see what was going on up at Lincoln. Mr. Rasmussen replied no, the bulldozer was ready to go. Whereupon Congressman Battin told the Regional Forester that, ‘By God, we had better have ten days.’ At this time, I believe the tide turned in our favor.”

On April 19, 1963, some 300 people jammed into the small Community Hall in Lincoln to hear the Helena Forest Supervisor discuss the plan. Ground rules were set; supporters and opponents were to alternate and there would be no voice vote at the end of the meeting. Opponents of the development plan felt they had been “gagged,” and a “near riot” took place. The level of bitterness began to increase dramatically. The association’s membership grew, and it soon received the backing of the Montana Wilderness Association, the Wilderness Society and the Montana Fish and Game Department. Senator Lee Metcalf wrote the Forest Service asking it to delay the project. During the next several months, the Forest Service received no letters supporting its plan. The timber industry had expressed initial approval of the timber harvesting but was heard from less and less as the controversy grew.

Cliff Merritt, the western regional representative of the Wilderness Society, used the backcountry as a boy and when he saw a Forest Service road stake in his family’s camping area he came to the sudden “violent” conclusion that they “…would build a road there over my dead body.” Merritt was a principal in the effort to get statutory protection for the area.

Robert Morgan, the new Forest Supervisor of the Helena National Forest, after looking over the situation, decided to postpone the development until “absolutely necessary.” In a tactfully written memo in January 1964, Morgan told his superiors that although there was some passive support for the Forest Service’s plan, “…we will get no active support from the man on the street.” Stating the plan was “basically very sound,” but that it was open to question on several points, he pointed out that the agency did not have a complete timber inventory of the area, that some timber of marginal quality had been sold, leaving an occasional ‘mess “behind, that neighboring National Forests were not fully coordinating their plans with Helena’s and that the presently developed campgrounds around Lincoln were not being fully used. Morgan counseled the Regional Office that the Forest Service could probably win the backcountry battle if it were willing to go all out, but in the process, it would pay a severe public relations price, which might jeopardize some of its other programs in Montana.

This “compromise attitude” was not well received in the Regional Office which wanted to begin road construction as soon as possible. Over the next few years Morgan heard some rough words from his superiors, who questioned his loyalty and felt he had caved into local demands. When the Lincoln Backcountry Protection Association met in February 1964, Cecil Garland convinced its members that because they could not get the Forest Service to commit to a 10-year moratorium on the road building, the goal of their organization needed to be changed. Garland advocated calling for a wilderness designation for the area and that the wilderness be expanded to 200,000 acres to take in the Scapegoat Mountain region, which adjoined the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

In April 1965, Democratic Senators Lee Metcalf and Mike Mansfield introduced a bill to protect 75,000 acres of the Backcountry under the Wilderness Act. Montana conservationists approached Republican Congressman Jim Battin and told him about the Metcalf-Mansfield bill and that there were more acres that could be included. Cliff Merritt remembers, “Big Jim had his feet on a desk and when he heard this, they came down fast … Jim saw this as an opportunity to leapfrog members of the other party. “Battin introduced his own bill calling for a 240,500-acre Lincoln-Scapegoat Wilderness. Metcalf and Mansfield who, Merritt concedes, had not been fully informed about the situation, soon switched their support to the Battin bill.

The Lincoln-Scapegoat bill was the first strictly citizen wilderness proposal made after the passage of the Wilderness Act, which mandated the Forest Service do a study of all their primitive areas for possible inclusion in the Wilderness System. Since it did not involve the expansion of a primitive area, the Lincoln-Scapegoat proposal was not explicitly covered by the study and review procedures of the Wilderness Act. The unique, potentially precedent-setting nature of the bill was one of the main reasons why its passage was delayed until 1972. The Forest Service leadership in Washington was concerned it would unleash similar proposals at a time when its work force was committed to finishing on schedule the primitive area reviews.

Tom Edwards, a former schoolteacher and outfitter in Ovando for many years, was an early member of the Lincoln Backcountry Association, he traveled twice to Washington, DC, to testify before congressional committees and gave this heartfelt eloquent testimony on behalf of the Lincoln-Scapegoat. “Into this land of spiritual strength, I have been privileged to guide on horseback literally thousands of people … I have harvested a self-sustaining natural resource of the forest of vast importance. No one word will suffice to explain this resource but let us call it the ‘hush’ of the land. This hush is infinitely more valuable to me than money or my business.”

As Bob Morgan later recalled, the 1968 hearings were “disastrous” for the Forest Service. Pointing to severe erosion caused by road construction in an area near the Lincoln-Scapegoat, Senator Metcalf testily asked Morgan how the Forest Service “could justify that!”

Morgan could only reply, “I can’t.” Soon after the hearings, the Forest Service published a new plan for a 500,000-acre area, which included the Lincoln-Scapegoat. The plan called for some land to be administratively protected as “backcountry” and for the construction of a 75-mile scenic Continental Divide Highway through the Lincoln-Scapegoat. Local environmentalists were not placated.

The Forest Service was becoming annoyed over an issue, which refused to go away. In early 1969, this frustration moved Regional Forester Neal Rahm to tell a meeting of the agency’s leaders that a “backcountry” land category, intermediate between complete wilderness and developed campgrounds, was needed. “We have lost control and leadership in the sphere of Wilderness philosophy. Why? The Forest Service originated the concept in 1920, and practically, has been standing still since about 1937 … Why should a sporting goods and hardware dealer [Cecil Garland] in Lincoln, Montana, designate the boundaries for the 240,000-acre Lincoln Backcountry addition to the Bob Marshall … If lines are to be drawn, we should be drawing them.” His remarks were the first indication that the Regional Office was bowing to the inevitability of wilderness designation for the Lincoln-Scapegoat.

One month after Rahm’s remarks, Chief of the Forest Service Ed Cliff told the Senate Interior Committee that the Forest Service would take another look at the Lincoln-Scapegoat. Plans for development were now permanently on hold. Cecil Garland relates that Congressman Battin asked him to draw up the boundaries for his wilderness bill.

Over a bottle of cheap whiskey, Garland and Forest Service men Lloyd Reesman and Bob Brown drew the lines for the future Scapegoat Wilderness.

Two years later, the supervisors of the Helena, Lolo, and Lewis and Clark National Forests drafted a wilderness proposal, based on the boundaries recommended by these three “cartographers,” which the Regional Office accepted. The Senate passed the Scapegoat Wilderness bill in 1969 and sent it to the House, where it was accidentally referred to the Agriculture Committee rather than the Interior Committee, thus arousing the ire of Chairman Wayne Aspinall who may have suspected an attempt to circumvent him. When he finally received the bill, Aspinall delayed reporting it out because the US Geological Survey had not conducted a mineral survey of the area as called for by the Wilderness Act.

Cecil Garland recalls how Aspinall was persuaded to support the bill. “I had just left the House Office Building and Congressman Wayne Aspinall, the powerful chairman of the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee; he had told me he would ‘kill’ my bill. I relayed this message to Senator Mike Mansfield who listened quietly and then said, ‘Ceace, you go back to Montana and tell the folks we’ll get the bill passed, that there’ll be a wilderness there some day. Some day there will be something that Mr. Aspinall will want, and we’ll be there.’ We shook hands and I walked with him to the Senate floor where a great fight was being waged over Vietnam.

“Later when Congressman Aspinall became fully committed to the passing of the bill, I asked him why he had decided to help us. His reply was, ‘Son, you’ve got one powerful Senator,’ and I knew what he meant. I knew Mike had not forgotten.”

In 1972 the Scapegoat Wilderness became the first de facto wilderness to enter the National Wilderness Preservation System. As mentioned earlier, the Forest Service opposed the Lincoln-Scapegoat proposal because it did not want to disrupt its timetable for primitive area reviews. The Regional Office was also concerned that if the Backcountry Association were successful there would be petitions for numerous other de facto wildernesses surrounding the Bob Marshall Wilderness. Several years after the passage of the Scapegoat Wilderness bill, Morgan, with the congratulations of the Regional Office, received an award from an environmental group for his part in preserving the Lincoln-Scapegoat area.

For decades the Forest Service had tried to insulate itself from local demands on the national forests in order to carry out its mandate to protect them in the national interest. These pressures usually came from groups that wanted to use them in ways that could have been detrimental to their long-term well-being. Environmental organizations and many in the general public supported the Forest Service when it resisted these demands. In the case of the Lincoln-Scapegoat, local pressure was applied, not to hurt the forest but to protect it completely. The Forest Service fought this demand in the same way that it would have fought demands to overcut or overgraze the area. The difference was that here the Forest Service was operating without public support.

This conclusion, however, must be qualified. A strongly professional organization, such as the Forest Service, is open to internal debate. Without the dissenting voices of Bob Morgan and the Lincoln District Rangers who served under him, roads would have been built in the Lincoln-Scapegoat long before the Scapegoat Wilderness Act of 1972.